Random Encounters in Small Dungeons

Play review of Tomb Robbers of the Crystal Frontier

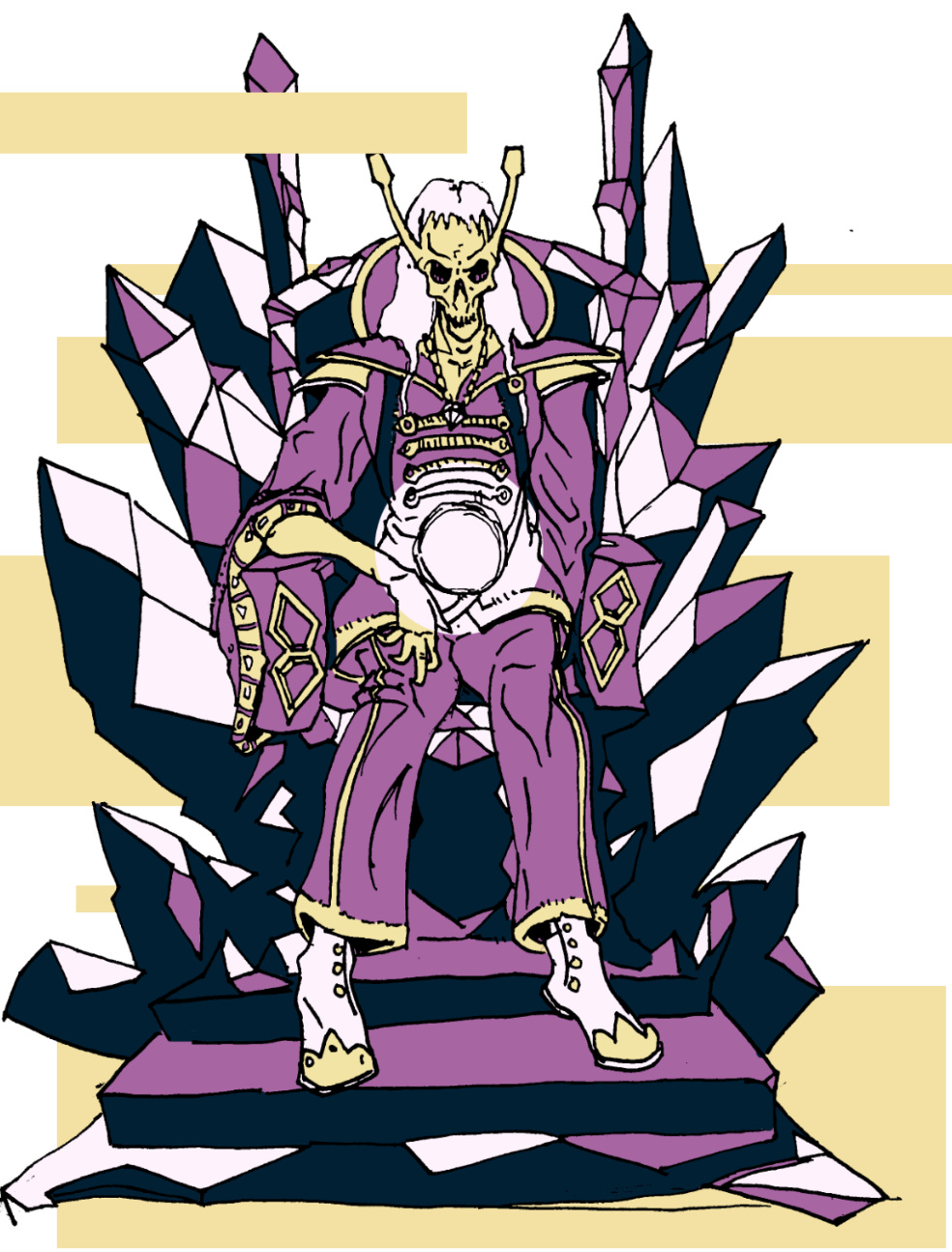

Recently I ran Tomb Robbers of the Crystal Frontier in two sessions (spoilers below). I used Electric Bastionland for the ruleset, using this conversion. Tomb Robbers is an oft-recommended adventure, and for good reason: it’s a very complete module, presenting an evocative and interesting science-fantasy ‘wild west’ setting. It focuses on a main dungeon, but also provides a starting town and region, a secondary dungeon, and several setting-specific spells and magic items. Rather than pretend that tomb raiding is a heroic endeavor, the setting is a cutthroat, gold-rush frontier, and in that way uses the more amenable idiom of the western as context for adventure. Nevertheless, the actual site of adventure—a crystal space-tomb fallen from the sky—is still fantastical. It’s specifically written as an introduction to dungeon crawling, with notes on playing style and an emphasis on problem-solving. Every room is lethal, including TPK possibilities not just from the monsters but also the environment itself, either in a quick way (ceiling lasers) or slow way (crystal poisoning causing ability loss).

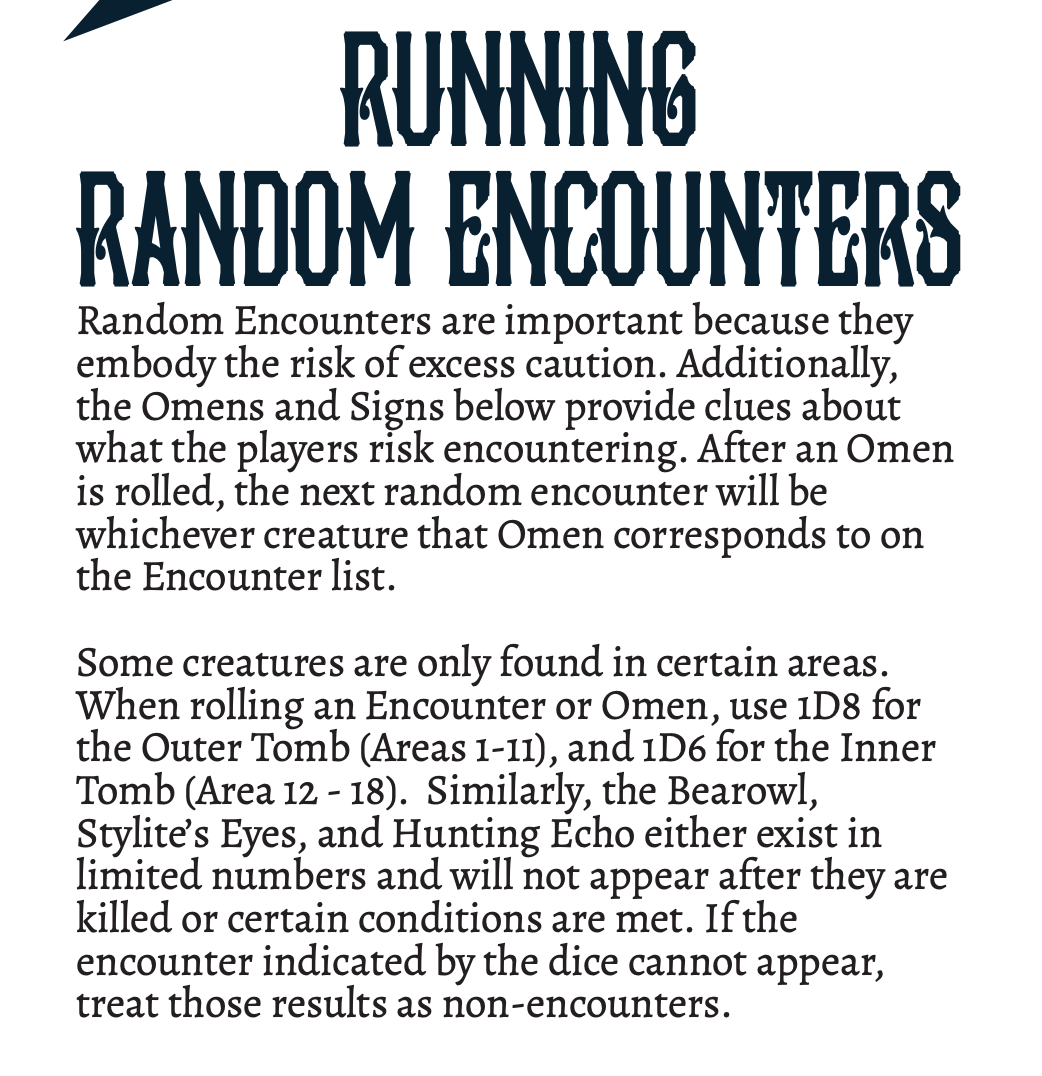

I think our experience was good, though there were a couple things we struggled with. Mostly these can be resolved by being explicit about the osr playstyle: emphasize that everything here is really deadly, that characters need to be motivated by collecting every scrap of treasure, that they need to describe where and how they approach the environment while searching, and that risks only lead to the possibility of reward, but must are always balanced against danger. That danger often takes the form of random encounters, which, as the module says, “are important because they embody the risk of excess caution.”

The random encounters were an area that I struggled with as a GM, and this is the topic of this post. This was not due to the module itself. Not only does the module provide advice and the reason for running random encounters (as a time pressure), there are 8 fully detailed encounters with information on how to interpret reaction rolls, omens that players get before being confronted with the encounter, and stats, all of which take up three full A4 pages. Rather, I think the problem I’m facing has more to do with the logistics of random encounters in small dungeons.

The Importance of Dungeon Size

Classic dnd rules make the most sense, I think, in the context of large and mega-dungeons. This is where the full leverage of risk and reward from encumbrance, light sources, movement speed, and time management come into play. My non-controversial hypothesis here is that the mega-dungeon was the locus of play for the early hobby, and the more you move away from that the less the particular rules make sense or at least the less they matter.

On the other hand, most of my OSR material takes the form of the A5 zine. Some of the included dungeons might be of decent size, like the Necrotic Gnome adventures which might be up to 60 rooms. Many, however, are more on the scale of 10-30 rooms, or depict regions with several locations of <10 rooms. Then there are even shorter forms, like one page dungeons or Mausritter pamphlets which also have <10 rooms. I find that running random encounters in these scenarios present several problems that would be less pronounced in a larger dungeon.

Density and Noise:

Tomb Robbers is about 20 rooms, but each one is fairly dense with things for players to interact with. There’s treasure in the walls to be extracted, sarcophagi with dangers or treasure, environmental/navigation hazards, in addition to various monster lairs. A megadungeon might have a lot of breathing space—empty rooms, corridors, large distances to be traversed. This is simply not present in Tomb Robbers. This level of density makes exploration fun, as each room presents at least one new challenge. But when one adds in the challenge of an ‘unrelated’ random encounter, sometimes the experience gets cluttered.

For example, in one room players were dealing with a lair of spiders in one corner, and a potential mummy in another, and I rolled a random encounter. While it might be fun to gauge how these different monster groups would react to one another (maybe the players could use it to their advantage!), it did present a scene where a lot of things were going on at once, which can be difficult to convey and manage for the GM. Similarly, omens/signs of a random encounter can be more confusing for players if they fail to distinguish them from whatever is happening within a given room

Distance:

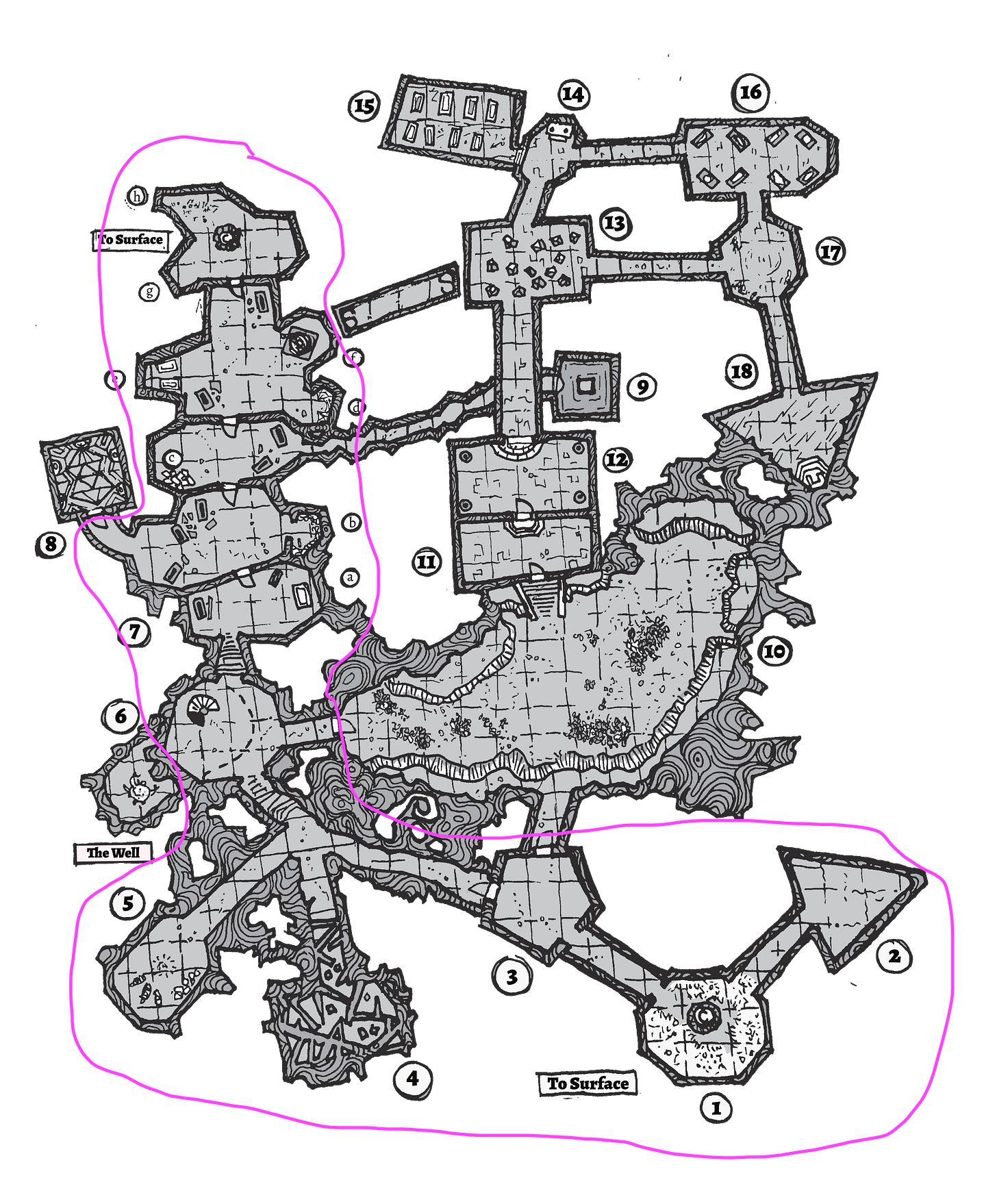

In b/x, random encounter distance is 2d6x10 feet. Let’s say that’s about 60 feet on average. Again, in a sprawling mega dungeon, this allows for a party to notice a possible encounter and choose if and how to fight, evade using dungeon loops, or hide. However, take a look at the scale of the Tomb Robbers map. An ‘encounter’ at such a distance may be two or more rooms away, rooms separated by closed doors and each room containing their own lairs or traps which could affect monster movement. If you roll a random encounter and the players notice, the only sensible thing to do is to place the encounter in the next room, which might only be 10 feet away, which gives the players far fewer options regardless of reaction roll. Especially given the deadliness of the combat here, when I ran the second session I always took a beat before breaking into combat to allow for them to solve the problem in an interesting way.

Fuzzy realism:

In a large dungeon, a wandering monster is just that—a monster that is wandering. It might be two orcs from the faction clear across the dungeon’s first floor. It might be an ooze that are anyway always lurking in the shadows. Or it might be a creature from a different floor all together. In other words, the check simulates the living underground environment.

However, the environment of a dungeon the size of Tomb Raiders is far more cramped. The result is that creatures either just pop into existence, coming from previously explored areas, or are part of a roster coming from an existing lair. The latter is fine, good even! But it does add to the tracking the GM has to do. For example, take a look at the map of the dungeon again. There is a “bearowl” lairing in room 7-h at the top left of the map. However, my players encountered the bearowl in room 7-b, which stalked them as they were spending 12 turns (!) faceting some crystal in room 8 to free an important NPC. I ruled that the bearowl eventually got disinterested and walked away. But which way did it walk? Apparently north, back to its lair, because that’s where they later found it. Let’s put aside the fact that this beast is apparently opening and shutting bronze doors to move through these spaces, and that it doesn’t interact with the other monsters or traps here. The range of areas where the bearowl could go (circled in pink) is a quite small and basically linear section of the dungeon. As a GM, once you introduce it via random encounter, you have to track its movements in a dynamic way. The roll no longer simulates the living breathing environment; rather, this is now part of the GM’s cognitive load.

Solutions

I fully accept that all of the above might just be a skill issue on my part. But I do think there is at least a little tension between the random encounter roll as designed and implemented in the context of mega dungeon play, and the smaller and denser adventures featured in many OSR zines. Thus, there might be a better way to design random encounters for small dungeons. I don’t have any good solutions at this point, but here are some thoughts

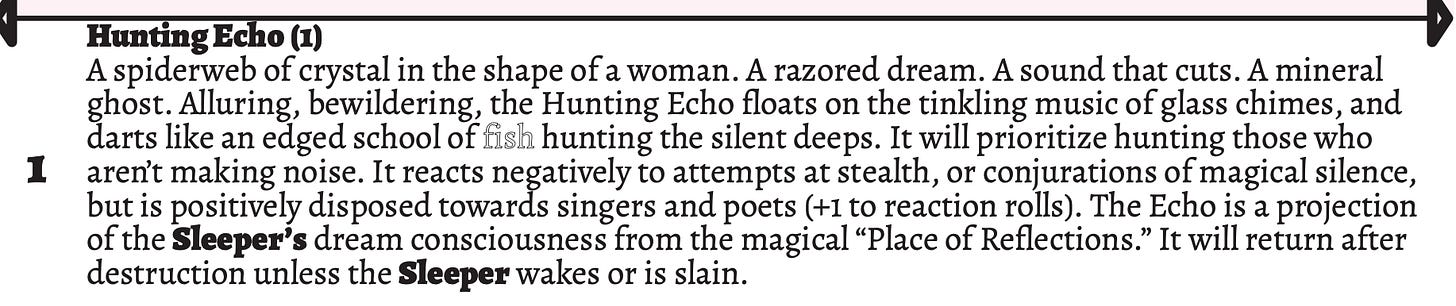

More weight on omens, signs, happenings, and non-combat encounters: One of the encounters from Tomb Robbers is a “hunting echo,” which is the dream consciousness of an important NPC. This is great, but in so far as it is a “hunting” echoes, it is an encounter that leads toward combat. In fact, being invisible and stalker-y, it leads to surprise combat, which is the least interesting option. And, of course, it’s deadly, with half the damage it takes being reflected back to the attacker, leading to the demise of one hireling in our group. This would be more effective and evocative as a social encounter, as the NPC tried to communicate with the PCs via their weird dream thing.

Clocks: That solution, however, doesn’t contribute to the risk-reward purpose of random encounters, wherein spending time searching for treasure or secret doors comes at the potential cost of a resource-draining encounter. What if we borrowed clocks from Blades in the Dark here? Every time the PCs made loud noise, spent more than a turn doing in one space doing something, or refused to move, the GM would mark a segment on a (non-player-facing) clock. When the penultimate segment was filled, they got an omen of danger. When the clock was full, the GM rolls random encounter. It might be an anathema to ditch the randomness of a simulated environment for something that forces an encounter, but maybe this is less of a problem if we’ve determined that random encounters in cramped environments don’t ‘simulate’ much to begin with.

Timers: For small dungeons, maybe we give up on using random encounters (and for that matter torches) as a timer to put pressure on the players. What are other ways to create timers? For this dungeon, the environment itself is described as deadly. What if players had to make a check every X turns or suffer another level of poisoning? This would mean they would have a limited time to get in, get what they need, and get out.

These are my vexations. Anyway Tomb Robbers is overall great. Would recommend, would run again. Oh, and, great art!