Mythic Bastionland

On Hybrid Games

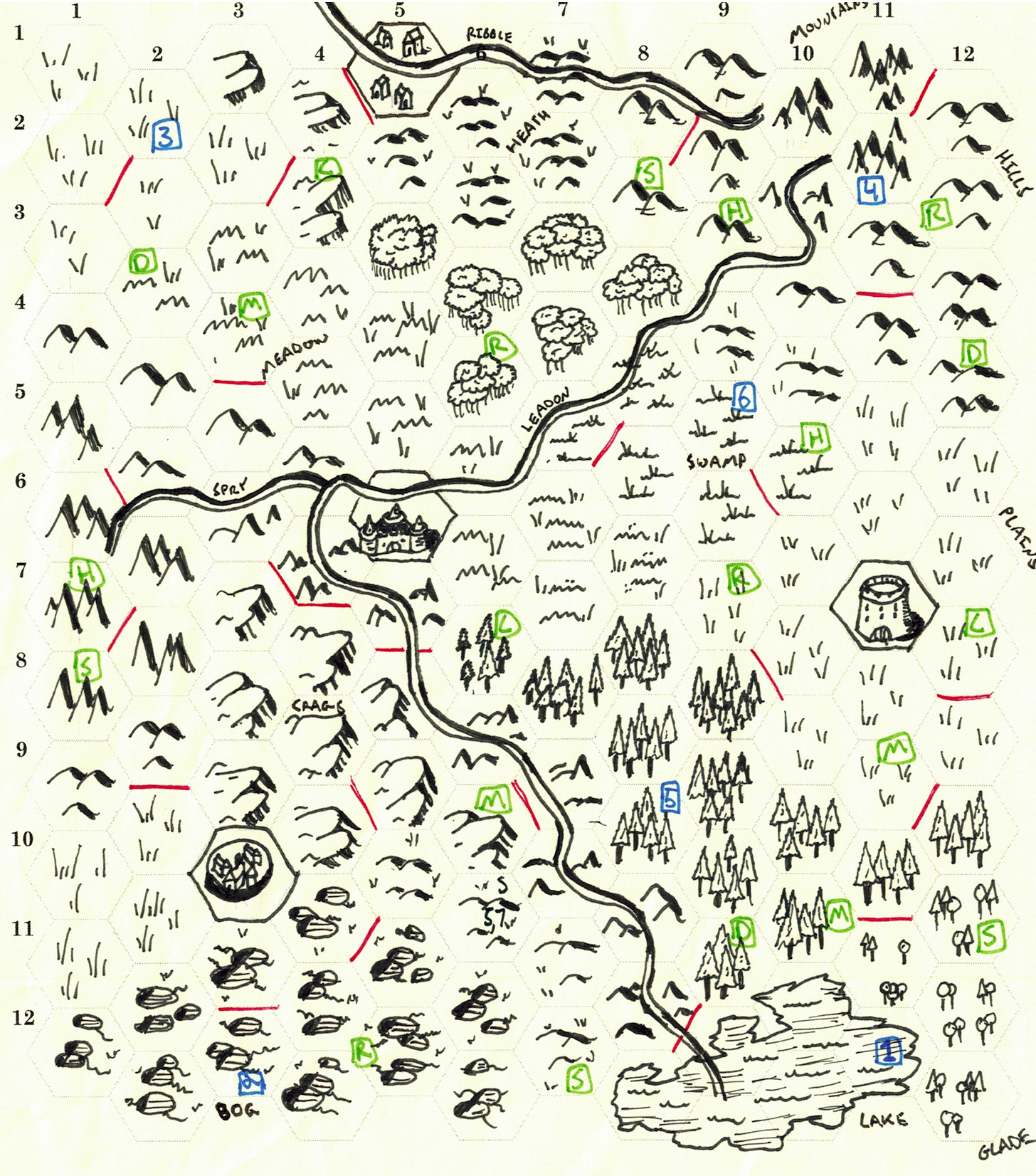

Last summer I was able to run a short campaign of Mythic Bastionland by Chris McDowall. What I really found interesting about this game was the way that it hybridizes various kinds of play experiences together in a way that still felt cohesive. Our game was highly emergent with very little prep needed on my part (and a lot of what I did manually prepare can now be created using this generator).

On the one hand, Mythic Bastionland (MB) has many hallmarks of an OSR game. The mechanics as such largely build on the stripped-down rulesets of McDowall’s Into the Odd and Electric Bastionland, with characters consisting of three ability scores, hit protection, a few items, and a custom background. It is a hex crawling game, with standard procedures for both map generation and movement/exploration on the map. It leans heavily on random tables to generate content within hexes. There are rules for warfare and domain management.

Combat is still a focus of the game, and has been built out with a system of feats and gambits by which players can add effects to their attacks. This was particularly fun, as players tried to collectively strategize how to use their dice to protect themselves, hinder their opponent, and control movement; yet, the whole combat procedure was simple to run in theater of the mind. I only broke out a grid for the final battle, which actually featured undead armies launching a siege attack of the realm’s major holding, with players defending.

On the other hand, MB diverges from common dnd expectations in a number of ways. Though the focus of the game is hex crawling, this is not a game that is worried about managing resources like food. Instead, the danger of wilderness exploration is balanced by the fact that ability scores can only be restored under particular conditions. Moreover, there are not really ‘random encounters’ as such. Instead, what the PCs do encounter are “omens” from a set of 5 or so “myths” that they have to eventually resolve. These myths are essentially self contained factions who progress their goals as the players explore, with each omen being a small scene of this progression. The result is that the referee is constantly feeding bits of (often obscure and quixotic) narrative to players, narrative that prompted by exploration and yet generally untethered to a particular location on the map.

This produces a somewhat phantasmagoric situation in which the drama of the setting works to envelop the PCs, regardless of what direction they go. For example, the PCs in my game encountered the third omen of “The Dead” myth, which read as follows:

“Under a Seer’s orders, a graveyard is being burned as a precaution aginst the restless dead. Acolytes scatter dried herbs. Five great red vultures circle” [with statblocks for the vultures, in case]

They did not have to march into any particular hex to reveal this scene, nor did I have to prepare the scene as a “clue” in order to railroad them toward a particular direction. In this way, MB feels more similar to story focused games that present players with scenes rather than with spaces to be procedurally explored. At the same time, the scene was introduced via an exploration procedure, and could be resolved with the familiar hp-draining, damage-rolling combat.

It’s certainly not for everyone. Players who want a standard hex crawl that takes place on a more objective terrain might be annoyed with their inability to mitigate danger via resource management, as the myths of the game constantly become an unavoidable center of attention. The way the myths are only lightly tethered to location further frustrates planning. Time can shift forward dramatically even between sessions, creating openings for character growth that essentially happen off-screen. Referees, meanwhile, might balk at the rather fragmentary presentation of the myths. They are more scenic vignettes rather than comprehensive faction summaries, and require a good bit of improvisation.

However, to me it proved that one can put a focus on narrative without abandoning procedural exploration, tactical combat, and referee-neutrality (and without linear railroading, obviously). The stakes of our MB game felt more substantive and less cloying than, say, a game of Dungeon World. MB is not about producing Arthurian stories, but much more about playing in a vaguely Arthurian world (though our reference point more often ended being Elden Ring, incidentally).

Anyway, I actually wanted to make this post mostly about the bartering system in the book, and how that affected our game in sometimes hilarious ways, but I guess that will have to wait for another post!