Are linear adventures railroads?

Yes

“The difference between a railroad and linear adventure is vast,” said James Haeck in a recent episode of the “Eldrich Lorecast” podcast. In this context a “linear adventure” means the kind of very common trad campaign play, either from a purchased adventure-path product or made at home. These adventures are event-based plots that have a set ending point, and, especially in a published book, story beats that the characters encounter in a pre-determined structure. All of the combat encounters in this structure are “balanced,” which does not mean that they will be fair fights but that the characters at the appropriate level will likely succeed unless there is an unlikely preponderance of bad decisions and/ or bad rolls, or perhaps if the GM decides that a character death would be narratively meaningful.

That’s all stating the obvious—the qualities of adventure path play are well known and form the core of the hobby. However, writing out such a description makes it rather obvious that these “linear” campaigns are, in fact, railroads. To greater or lesser degrees, the adventure decides in advance how the story will begin, build, develop, and end. You can flip to any random page in an adventure path and know the level and loadout of the characters, their location, the major events of the story thus far, and even the major decisions of the PCs, precisely because decisions of consequence will not be left to the PCs. A fair amount of trad gm advice has nothing to do with not railroading the players, but rather how to soften the rails, giving players an illusion of decision-making freedom while always guiding them back to an already-decided narrative. We can maybe call it a freeway rather than a railroad: you can choose your lane, maybe you can even stop for a rest break now and then, but you are traveling along a particular route and stopping a particular destination.

In a previous episode, the “lorecast” unwittingly made this point explicitly. First, guest Mike Shea discussed giving players a choice of three quests that all tie into the larger plots of a villain. This is not inherently bad advice, so long as the GM is also open to other activities the players want to pursue (he’s advocated such an approach before). However, then host Shawn Merwin chimes in with some of the worst GM advice I’ve heard in a while. He says

And the good part about that is if you do have a player—I’m not going to call this player problematic I’m going to call this player challenging [laughter]. The player is challenging because you set up these three quests, and they want to know who the mayor is and if they can romance them. Well, you can still then just say ‘yes, you can go talk to the mayor...’ Now the mayor, who I didn’t even think of, is a servant of the dragons who are ruling [the BBEG]. I’m going to keep putting that quest in front of you. It’s something that is going to lead you toward the north star that we’re always heading to.

In other words, railroading. Here, when a player shows even a minimum level of agency or curiosity about the fictional world or does anything other than the very limited choice the GM sets in front of them, they are immediately directed back to the plots of the singular villain, which is the only thing they can engage with. The PCs have now found themselves in a kind of Truman-show scenario, where the world is just plywood set dressing for the GM’s already made story. All this is perhaps not surprising, given that earlier in the episode he says that “stepping on player agency isn’t about taking the story where you as the game master see it going,” even though unilaterally directing the story to a particular conclusion is literally an example of stepping on player agency.

It’s also not surprising that his advice is framed around a player who is “problematic/challenging,” because railroading is essentially an adversarial style of play. The player is ‘challenging’ to deal with because they insist on the premise of TTRPGs, namely that the characters exist in a living world and can do anything within the physical and metaphysical bounds of that fictional world.

Feels like

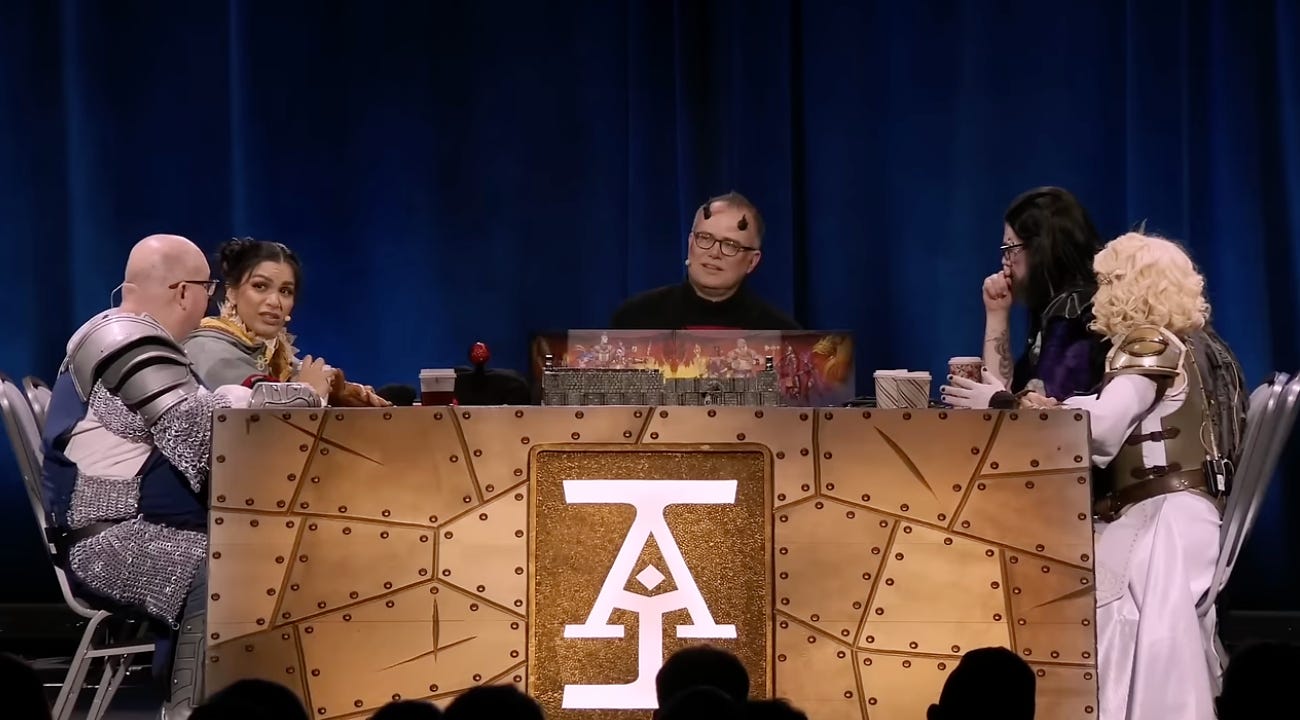

The podcast where Haeck makes the above claim is explicitly about published adventures, and in that way is not about the merits of linear adventure but how to write them. Indeed, I think that adventure writers are more canny in how they present linear adventures than they were back in the days of OG Dragonlance. The mistake, however, is thinking that these techniques make the linear adventure something other than a railroad/freeway. Rather, the focus is on how to make the railroading “more palatable,” as Haeck says.

Their examples are mostly taken from video games and interactive fiction, modes of storytelling that do not feature a live human being that can dynamically respond to the audience and invent new fiction as a result. Rather, GM prep is treated like a questline would be in a crpg, with only so many branching options possible. Guest Erin Roberts compares a linear adventure to “choice models” in interactive fiction where “the left and right [choice] are the only ones available and they are different enough that it feels like you got to make—because you did—actually got to make a substantive choice, but in the end those branches eventually get you back to some major stream.” The interruptive slip is interesting, because it is almost like Roberts hears herself describing a false choice that merely “feels like” a real one. Haeck similarly discusses how the gameplay of Breath of the Wild makes players “feel like a genius” for solving a puzzle. Host Ben Byrne then describes running a Witcher-style monster hunt in a ttrpg,

you will find the monster, you will fight it, and because, talking in a 5th edition context, your characters are generally all pretty good at fighting things, you will probably defeat it. But, if you engage fully in the story, and you succeed the checks that are put along the way, you discover [a fuller backstory]. That’s the skill of players engaging with the game fully. That’s not mandatory to get the entire story, [but if you do] you feel like a frickin genius…it’s not hard, it’s not particularly difficult to figure out, it makes you feel really proficient and really skilled to engage in those systems, but you don’t have to to be able to complete the narrative.

That is, the choices you make to research the monster or not, or to take path A or B, are ultimately immaterial, as success is guaranteed (and they insist on including enough choices that the PCs can always ‘fail foward’ to the next moment in the plot). But one must still include the illusion of choice, because it is important the players feel like their actions and decisions are impactful.

Trad icon Matt Colville has expressed similar sentiments in the past about the value of linear adventures, but interestingly, rewatching his video on the topic indicates a point of view that is clearer and more nuanced than what the Lorecast crew provides. For one, he calls out much of the above (e.g. a branching path that leads to the same end point) as what it is, i.e. railroading. It shows how, when one accepts the premise that constraining choice is necessary to tell a satisfying story, you can easily slip to a situation that Merwin describes, where any attempt to engage as a fictional character in a living world is “problematic.” A few steps further, and we have what Justin Alexander calls a cargo cult adventure.

But Colville too uses gentler terms to describe a similar activity; in his parlance, the GM “guides” or “herds” the players back to the prepared content. In fact, that there is prepared content ultimately leads to a metagame question: do you want to play dnd tonight or not. The adventure path GM ought to try to resolve this question subtly in game, by guiding the players in a particular way, but ultimately it’s a question of there being nothing to play without (often extensive) prep.

Here we are now, entertain us

Perhaps I shouldn’t say the above is bad advice, however. I’m sympathetic to the refrain from the trad community that linear adventures are different than railroading because of the severe connotations of the latter. Railroading at its worst suggests a kind of anti-social behavior, a GM on a powertrip who insists on imposing a singular vision on a shared activity. Whereas, many people love adventure-path play, and they are not wrong to love it. They perhaps experience such play as collaborative and challenging even if at some level they know or even expect to be led from plot point to plot point via encounters that they will overcome.

The adventure path is like a magic trick then. We know that magic isn’t real, but we suspend disbelief long enough to be entertained. The role of the GM is be the entertainer. World building may help the GM be a convincing entertainer, but ultimately their job is to provide fun set piece moments that allow for character expression. OC-style character expression, meanwhile, is where the player has the most fun. It doesn’t matter that we know, in advance of the hour long combat, that the divine smite will kill the hobgoblin, because the fictional act is a way to express character. The plot that happens after can be left to the GM’s perhaps overworked. imagination

.